Malcolm Gladwell

is in his natural habitat – a cafe in New York's West Village, down the

street from his apartment – engaged in a very Gladwellian task:

defending Lance Armstrong.

The bestselling author of The Tipping Point

and Outliers, who despite all appearances just turned 50, has a tendency

to hoist both arms aloft like a preacher when a topic inflames him.

And

the topic of doping in sports does. Why, he wants to know, is it OK to

be born with an abnormality that gives you surplus red blood cells, like

the Finnish Olympic skiing star Eero Mäntyranta, but not OK to reinfuse

your own blood prior to competing, as Armstrong apparently did?

Why are baseball players allowed performance-enhancing eye surgery, but

not performance-enhancing drugs?

"Imagine," Gladwell says, "if all the

schools in England had a rule that you can't do homework, because

homework is a way in which less able kids can close the gap that Nature

said ought to exist. Basically, Armstrong did his homework and lied

about it! Underneath the covers, with his flashlight on, he did his

calculus! And I'm supposed to get upset about that?"

David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants

by Malcolm Gladwell

This argument enraged various sports pundits when Gladwell made it in The New Yorker, where he's been a fixture since 1996. But it will presumably only enrage them more to learn that he doesn't fully believe it himself.

"When you write about sports, you're allowed to engage in mischief," he says. "Nothing is at stake. It's a bicycle race!"

As a serious amateur runner himself (just the other day, he finished the Fifth Avenue Mile race, in Manhattan, in five minutes and three seconds) he's "totally anti-doping … But what I'm trying to say is, look, we have to come up with better reasons. Our reasons suck! And when the majority has taken a position that's ill thought-through, it's appropriate to make trouble." His expression settles into a characteristic half-smile that makes clear he'd relish it if you disagreed.

Gladwell has always

excelled in this role as intellectual provocateur. At their best, which

is often, his articles and books force you to reappraise assumptions so

deeply held that you didn't realise you held them, and millions have

found the experience intoxicating.

What if the most successful

entrepreneurs aren't the risk-takers, but the risk-averse?

Might the

world's intelligence agencies be better off firing all their spies?

Is

there a good reason why there are multiple kinds of mustard, but only

one major brand of ketchup?

The point isn't necessarily to accept his

conclusions, but to be jolted – even if via the improbable medium of

ketchup – into seeing the whole world afresh.

This galls some critics,

who'd prefer it if Gladwell made smaller, more cautious, less dazzling

claims. ("The problem with the Malcolm Gladwell Piece," a New York Observer journalist once wrote,

"is that it always seems to contain phrases like 'the problem with the

Malcolm Gladwell Piece.'")

But it's also what stimulates audiences in

such vast numbers: Outliers reportedly commanded a $4m advance, and

dominated bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic for months;

while his live lecture events, which reliably sell out, have made him

the only person about whom the labels "rock star" and "journalist" are

both routinely used.

He's also responsible more than anyone else for the

birth of the modern pop-ideas genre, in publishing and beyond. "Without

Gladwell," Ian Leslie wrote recently at Medium.com, "no Daniel Pink, no Steven Johnson … no Brainpicker, no TED. I exaggerate, but only slightly."

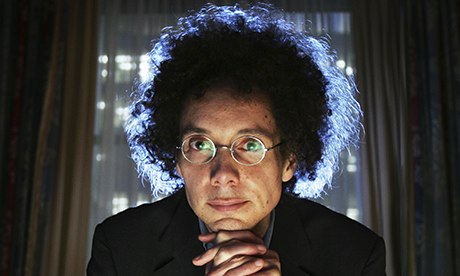

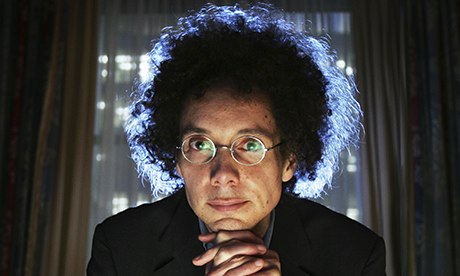

Gladwell in 2005. Photograph: Rex Features

Gladwell in 2005. Photograph: Rex Features

Gladwell will perform four more such events, in London, Liverpool and

Dublin, later this autumn. The occasion is the publication of his new

book,

David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants,

which is published in the UK on Thursday.

There's a case to be made

that it's his best yet: on the counter-intuitiveness front, it's classic

Gladwell, but it's also more socially and morally engaged than his

previous work.

That title might smack of how-to-get-ahead-in-business,

but he's no longer focused on the secrets of marketing or corporate

success.

David and Goliath explores when, and why, apparent

disadvantages – poverty, personal setbacks, military weakness – turn out

to be advantages, and when advantages, like wealth or status, aren't

what they seem.

"The fact of being an underdog changes people in ways

that we often fail to appreciate," Gladwell writes. "It opens doors and

creates opportunities and enlightens and permits things that might

otherwise have seemed unthinkable."

The outcome of the original

David-and-Goliath clash wasn't a miracle, he argues: it's just what

happens when the weak refuse to play by rules laid down by the strong.

(Sample sentence: "Eitan Hirsch, a ballistics expert with the Israeli

Defence Force, recently did a series of calculations showing that a

typical-sized stone hurled by an expert slinger at a distance of 35m

would have hit Goliath's head with a velocity of 34m per second – more

than enough to penetrate his skull and render him dead or unconscious.")

"With

each book that passes, I think my personal ideology becomes more

explicit … and this one is a very Canadian sort of book," says Gladwell,

who was born in Fareham, in Hampshire, but grew up in Ontario.

"It's

Canadian in its suspicion of bigness and wealth and power. Someone told

me – did you know that there's never been a luxury brand to come from

Canada? That's never happened. That's such a great fact to have about

your home country."

Difficulties and afflictions

frequently foster creativity and resilience, the book shows.

Studies on "cognitive

disfluency" have shown that people do better at problem-solving tasks

when they're printed in a hard-to-read font:

the extra challenge

triggers more effortful engagement.

We meet dyslexics whose reading

problems forced them to find more efficient ways to master law and

finance (one is now a celebrated trial lawyer, another the president of

Goldman Sachs);

we learn why losing a parent in childhood forges a

resilience that frequently spurs achievement in later life, and

why you

shouldn't necessarily attend the best university that will have you.

(The answer is "relative deprivation": the further you are from being

the best at your institution, the more demotivating it is; middling

talents perform better at middling establishments.)

Conversely, having

power can backfire, not least because it tricks the powerful into

thinking they don't need the consent of those over whom they wield it.

In a compelling account of the Troubles, Gladwell argues that the

British were plagued by a simple error: the belief that their superior

resources meant "it did not matter what the people of Northern Ireland

thought of them". More isn't always more.

There's a reactionary

way to interpret all this: if the human spirit finds ways to triumph

over adversity in the end, does that mean we needn't worry about

poverty, prejudice, childhood traumas, and the rest? "In the 19th

century, people like [the industrialist] Andrew Carnegie did talk about

poverty being useful as a justification for doing nothing about it,"

Gladwell says.

"But if this book's interpreted that way, that would be a

disaster. I'm just trying to say that it should reassure us that the

inevitable traumas of being human do end up producing some good.

Otherwise, the human condition is overwhelmingly depressing.

" We used to

be genetic determinists, he says. "We used to say poor people had lousy

genes. Then we decided that wasn't OK, but we transferred the prejudice

to upbringing. We said, 'You were neglected as a child, so you'll never

make it.' That's just as pernicious. This book is anti-deterministic in

that sense."

It is hard to resist trying to understand Gladwell's own life

and background in terms of Gladwellian theories. Indeed, in 2008's

Outliers he does so himself, explaining, in line with the book's thesis,

how the right combination of effort and contextual factors – such as

her light skin – enabled his Jamaican mother, Joyce, to end up at

University College, London, where she met and married an Englishman,

Graham Gladwell. (She became a therapist, he a maths professor.)

When

Malcolm was six, they moved to Canada, to a heavily Mennonite community;

Gladwell imbibed that denomination's focus on social justice, while

excelling as a runner at school.

After a history degree in Canada, and a

couple of years at conservative magazines, including the American

Spectator, he joined the Washington Post in 1987 – where he spent a

decade accumulating the 10,000 hours of practice which, according to

Outliers, is they key to mastery in many fields.

He joined the New

Yorker in 1996, and published the original "Tipping Point" article that

same year, analysing the plummetting Brooklyn murder rate through the

lens of epidemiology. As has been frequently observed, the book,

released four years later, was his professional tipping point, too.

Blink, his 2005 book on the strengths and weaknesses of unconscious

decision-making, consolidated his status.

He has continued to

produce tirelessly since then, with little time, as far as one can tell,

for much in the way of a personal life. ("He's dated a lot of women. He

loves other people's kids. But he has work to do," his oldest friend,

Bruce Headlam, told the Observer a few years ago.

Gladwell charmingly

but firmly rebuffs all questions in this vein.) He lives in a book-lined

apartment on one of downtown Manhattan's loveliest streets, but has

often described his preference for a "rotating" approach to writing,

involving stints at several local cafes, in an effort to recreate the

ambience of a newsroom.

We are now sufficiently far into the

Gladwell era that the Gladwell backlash is well under way.

He is

routinely accused of oversimplifying his material, or attacking straw

men: does anyone really believe that success is solely a matter of

individual talent, the position that Outliers sets out to unseat? Or

that the strong always vanquish the weak? "You're of necessity

simplifying," says Gladwell.

"If you're in the business of translating

ideas in the academic realm to a general audience, you have to simplify …

If my books appear to a reader to be oversimplified, then you shouldn't

read them: you're not the audience!" (Another common complaint, that

his well-paid speaking gigs represent a conflict of interest, is

answered in a 6,500-word essay on Gladwell's website.)

A subtler

criticism holds that there is something more fundamentally wrong with

the Gladwellian project, and indeed with the many Gladwellesque tomes

it's inspired.

To some critics, usually those schooled in the methods of

the natural sciences, it's flatly unacceptable to proceed by concocting

hypotheses then amassing anecdotes to illustrate them.

"In his pages,

the underdogs win … of course they do," the author

Tina Rosenberg wrote,

in an early review of David and Goliath. "That's why Gladwell includes

their stories. Yet you'll look in vain for reasons to believe that these

exceptions prove any real-world rules about underdogs."

The problem

with this objection is not that it's wrong, exactly, but that it applies

equally to almost all journalism, and vast swaths of respected work in

the humanities and social sciences, too. You make your case, you

illustrate it with statistics and storytelling, and you refrain from

claiming that it's the absolute, objective truth.

Gladwell calls his

articles and books "conversation starters", and that's not false

modesty; ultimately, perhaps that's all that even the best nonfiction

writing can ever honestly aspire to be.

Gladwell once wrote an

article defending a playwright who'd lifted material from one of

Gladwell's own articles, so perhaps it's not surprising that he also

defends his former

New Yorker colleague Jonah Lehrer, who admitted fabricating quotes

in his book Imagine.

"In the classic sense of the word, it was a

hysteria," Gladwell says of the anti-Lehrer uproar.

"There was a kind of

frenzy about it that was disproportionate to the crime.

Jonah screwed

up, and he's the first to say he screwed up, but I'm puzzled by how much

vitriol was directed at him. If I was going to be psychoanalytic about

it, I'd say it has to do with anxiety within the world of journalism,

about its loss of authority: we think we're losing our place in the

world, and so we're hypersensitive about those who undermine that place

further."

Then again, Lehrer recently obtained

a new book deal: perhaps his new-found position as an underdog will benefit him yet.

The

most powerful section of David and Goliath concerns the climactic

battle of the civil rights movement in Alabama, in 1963.

In public,

Martin Luther King and his aides maintained a dignified facade, but

behind the scenes, King's organiser in Birmingham, Wyatt Walker, used

cunning to turn the movement's weaknesses into strengths.

By delaying

street protests until late afternoon, when Birmingham's black residents

were walking home from work, he led authorities to believe that

onlookers were actually protestors.

("They cannot distinguish even

between Negro demonstrators and negro spectators," Walker later

recalled. "All they know is negroes.")

By luring police into arresting

hundreds of children, they overwhelmed Birmingham's jails, turning

police commissioner Bull Connor's eagerness to arrest black people

against him.

Perhaps it wasn't "right", by some definition of that word,

to send children for arrest, or to engineer confrontations between

passers-by and police dogs –

-- but Gladwell argues:

"We need to remember

that our definitions of what is right are, as often as not, simply the

way that people in positions of privilege close the door on those at the

bottom of the pile."

Underdogs have to use whatever they've got. And in

the end, "much of what is valuable in our world arises out of these

kinds of lopsided conflicts … the act of facing overwhelming odds

produces greatness and beauty."

Details: malcolmgladwell-live.com